A couple of blog posts back, we touched on visiting the National Monument on Calton Hill and also its alternative names of ‘Edinburgh’s Folly’ and ‘Edinburgh’s Disgrace’. Though it has become an icon of Edinburgh, and as easily recognisable in the city’s skyline as the castle itself, few visitors know the story of this incomplete structure and the concept behind it.

The first mention of a National Monument dates from 1816, a little over a year after the Battle of Waterloo that had brought to an end more than 20 years of more or less continuous warfare with France. The idea was discussed at a meeting of the Highland Society of Scotland and various proposals put forward. One of the attendees that day was Lord Elgin, the man who had removed the decorative frieze from the Parthenon in Greece – the sculptures that would later become known as the ‘Elgin Marbles’. We cannot be certain that it was Lord Elgin who proposed a scheme to build a facsimile of the building that he knew so well but his presence at the meeting is surely significant.

By January 1822, plans for the royal visit of King George IV to Edinburgh were well in hand. Sir Walter Scott, active in both the organisation of the visit and the Highland society, considered that it would be the most perfect conjunction of circumstances if, during the visit, the king could lay the foundation stone of the new monument. An appeal for £42,000 was launched, signed not only by Sir Walter but also Henry Cockburn and Frances Jeffrey, among others.

For a season the idea of a modern Parthenon gracing the Athens of the North obsessed the middle classes of the city. The Edinburgh Review noted that many who just a twelve month before knew nothing of Greek architecture “now talk of the Parthenon and of peristyles and cells and intercolumniations and pediments with all the familiarity of household objects.”

It was proposed that the Memorial should be more than just a recognition of the war dead. There could also be catacombs where the famous and great of the future might be interred – a sort of Scottish Westminster Abbey.

In the event, the king declined the offer – probably because he was advised that Sir Walter would try to tap him for a donation. Indeed, the project ran into financial difficulties from the start. By April 1823 only £16,000 had been raised.

Parliament in London was approached for a grant of £10,000, partly on the idea that this was not merely a Scottish scheme but ‘A splendid addition to the architectural riches of the empire’. Parliament was not persuaded.

Nonetheless, it was decided that a start should be made. The architect chosen for the work was C R Cockerell, an acknowledged expert on Greek architecture and the obvious man for the job. However, the committee also decided that they should have a local man on site and additionally appointed William Playfair, already noted for his neoclassical work in the New Town. This was not the most happy of working arrangements and in the end, Cockerill was relegated to little more than supplying drawings while Playfair got on with the actual work.

The material chosen came from the Craigleith Quarry, near the city. Playfair had used this stone extensively in the New Town and understood the quality of the material. It took 12 horses and 70 men to move the larger pieces and work proceeded at a slow pace. By 1829 only 12 pillars had been completed – and that’s when the money ran out.

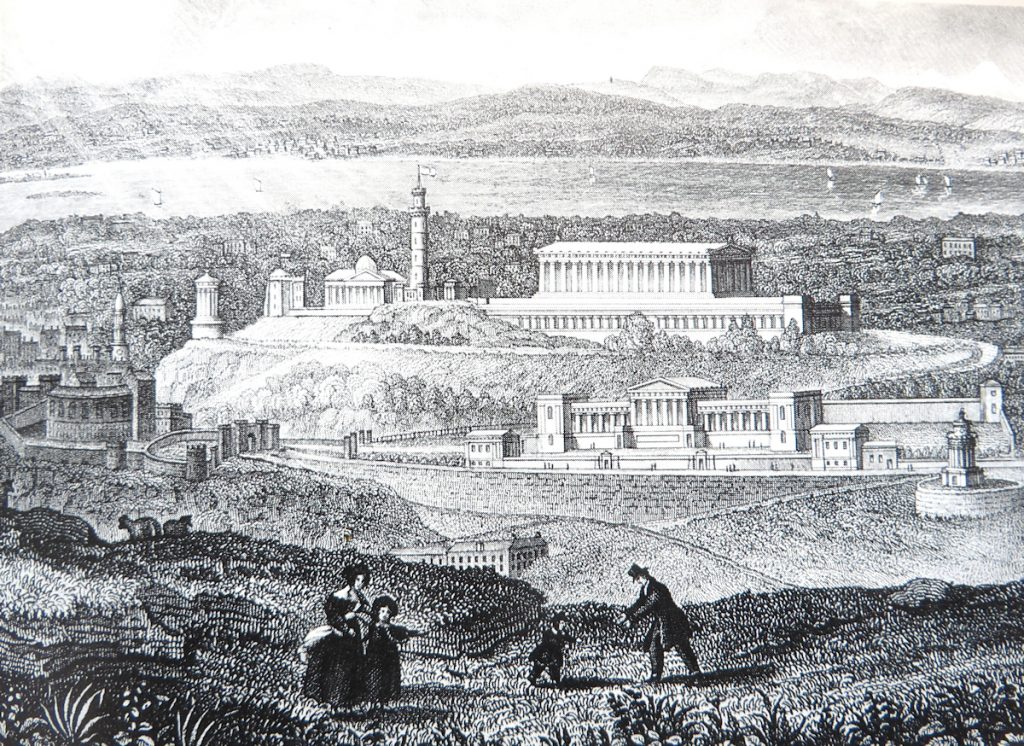

Courtesy of Edinburgh University Library

It’s since been suggested that the backers of the scheme understood when they started work that the building would never be completed. If true, one must admit it was conceived as the most awe inspiring folly in the land.

Rather inevitably, schemes to finish the building surface every few years and, just as certainly, come to naught, for those ideas are themselves flawed. They misunderstand the relationship the people of Edinburgh, and Scotland, have with the National Monument. We don’t see it as a failure or something shameful. It’s in the Scottish character to think big and go for the great prize, even if you fail, rather than be cautious and conservative to gain the lower honour.

The building, even in its incomplete state, may still fulfil the original concept. When we told the story above to a visitor, he stood for a moment regarding the columns and then said, “Now, when I look at this, I don’t see a bit of an old temple. I see a rank of Scottish soldiers, standing erect, ready to go into battle and do their duty.”

Which is perhaps more fitting than a completed temple filled with dusty memorials to lost lords and forgotten politicians.

Leave a Reply