Tucked away in a little triangle of land off Milton Street, and bounded on the other sides by the East Coast Railway line and Croft An Righ, is a development of modern apartment buildings called Tytler Gardens. To most people living there, the name probably means little but in fact, it commemorates a moment of aviation history, for it was from this very spot that Britain’s first, manned aerial flight was made. The man who accomplished this remarkable feat, and who is remembered in the street name, was James Tytler.

James was born in 1745, the son of the manse at Fearn in Angus. A bright lad, he did well at school and was then apprenticed to a surgeon in Forfar. In 1764, he came to Edinburgh to study medicine at the university. James was no doubt clever but he seems not to have been wise. Money – or rather, the lack of it – was to trouble James all his life and it seems to have started early, for barely a year later he signed on as ship’s surgeon with a Leith whaling ship, the Royal Bounty. He needed the wages as he had married, somewhat in haste, and had to pay for a wife and child.

After returning to Leith, he set up as an apothecary but the business was not a success and, with debts piling up, he was forced to flit to England.

By the time he returned to Edinburgh, his family had grown. He now had five children and to support them he employed a remarkable skill that he possessed. It was said, that he could edit a piece of prose as fast as other men could read it. Though a prolific writer himself, he was mostly employed by other writers and publishers to prepare texts ahead of printing. However, this work was far from steady and he ended up in the debtors’ sanctuary of Holyrood.

Eventually he found steady work in editing the second edition of that great work of the Scottish Enlightenment, the Encyclopaedia Britannica, as it was expanded from the initial three volumes to a more comprehensive twenty volume edition. The work was dreadfully paid – just sixteen shillings a week – and it would take Tytler seven years to complete, working long hours using an upturned washtub as a desk.

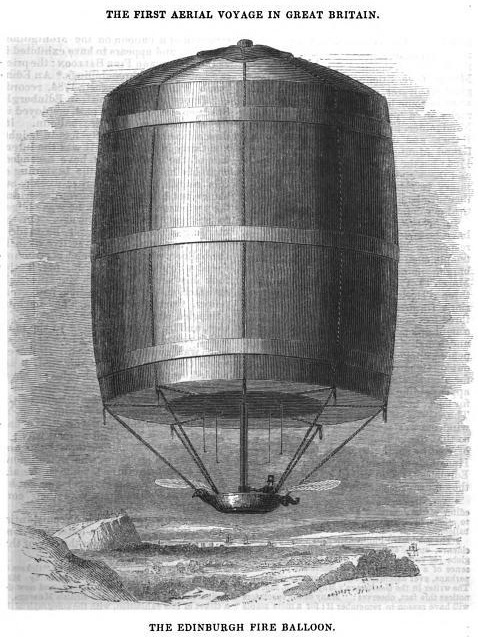

It was while he was compiling the section on the newly invented Air Balloons that he had his brilliant idea. The Montgolfier brothers had made the first successful manned flights in Paris in November 1783. The thought of flying enthused James Tytler and though almost entirely without funds, or any public interest, he decided that he would build and fly his own hot air balloon. It would be called, The Grand Edinburgh Fire Balloon!

He first built a model, and charged people sixpence to see it. He then set about making the real thing. At the time, June of 1784, Register House at the east end of Princes Street was still under construction and although it had walls, the dome was not yet completed; the empty building was the perfect venue to show off his marvel.

The Grand Edinburgh Fire Balloon was not the roughly spherical shape we might think of today but was more like a barrel some 40 feet high and 30 feet in diameter. The hot air was provided by a stove and Tytler proposed to ‘fly’ his creation from a wicker ‘boat’, made to resemble a bird and slung below the envelope.

By August 1784, everything was ready and the balloon was taken to the site of the present day Tytler Gardens, then a pleasure ground known as Comely Garden, and the first flight advertised to take place on the the morning of the sixth. Tytler however, had not taken into account Edinburgh’s notoriously capricious August weather. This, combined with some technical difficulties, prevented the balloon from rising. The crowd reacted in traditional Edinburgh style and attacked Tytler. He escaped, beaten but not downhearted, and determined to try again.

The balloon was next ready on August 25, and this time Tytler wisely decided that only a few people would be there to see the attempt. The fire was lit at an early hour and kept burning until mid-morning. Then Tytler climbed aboard and the tether ropes were released. The Edinburgh Evening Courant was there as a witness and reported, “…the balloon, together with the projector himself, and basket in which he sat, were fairly floated”.

Now that the Grand Edinburgh Fire Balloon was a proven success, a great (and paying) crowd turned out to see it fly two days later. This time, the balloon rose to around 350 feet and flew all the way to Restalrig. These flights were the first to take place in British airspace.

Another flight was made on August 31 but subsequent attempts all ended in failure. The press, ever keen to knock down someone they have built up, laughed at him and the public quickly lost interest.

A year later, the flamboyant Italian showman Vincenzo Lunardi would tour Britain with his aerial balloon show, including a flight of 46 miles from George Heriot’s School in Edinburgh to Ceres in Fife in a hydrogen filled balloon.

Lunardi was so popular that he created a craze in women’s fashion for balloon-shaped ‘Lunardi Bonnets’, which were even mentioned in a poem by Robert Burns. Tytler was almost entirely forgotten.

The money James Tytler made from his exploits seems to have vanished very quickly. He was soon back in Holyrood sanctuary, hiding from debt. He divorced, remarried, had more children, wrote more books but in 1792 was forced to flee abroad after being charged with seditious libel for producing an anti-government pamphlet. He went first to Dublin, then Salem in Massachusetts. It was there, one stormy night in January 1804 that he fell in the sea on his way home from an inn. Thus passed James Tytler, Scotland’s aviation pioneer.

Leave a Reply