Edinburgh is the greenest city in the UK (check out the image here) and a good part of that open space is made up by Holyrood Park. The main feature of the park is, of course, Arthur’s Seat, a wee piece of the Scottish Highlands transported to the city centre.

Despite its wildness, thousands of residents and visitors climb the mountain every year, something borne out by the fact that it’s ranked the number one thing to do in Edinburgh on Trip Advisor. The way is made easier for many of these walkers by a wide and gently sloping path that runs alongside Salisbury Crags known by the unusual name of the Radical Road.

There’s nothing radical about the road itself; neither its construction nor site are sufficiently out of the ordinary to give it such a name. In fact, it was the men who built it that earned the epithet, ‘radical’ and from them, it was transferred to the road. They were men who had lived through the decades of war, with first revolutionary, and then Napoleonic France. Those wars ended in 1815, following the Battle of Waterloo, but peace did not bring prosperity.

Britain entered a period of economic hardship. Many in Scotland saw this as a consequence of a corrupt political system that favoured the interests of a privileged few over the needs of the majority. They called for reform, and in particular the expansion of voting rights.

To take Edinburgh as an example, at this time, the Member of Parliament for the city was elected solely by the 25 magistrates of the City Council. The Right Honourable Henry Dundas MP, working with William Ramsay of the Royal Bank, would scrutinise the list of magistrates elect; men hoping to sit on the council. If he found the name of someone whom he thought would oppose him, he would ‘persuade’ the council to substitute a candidate of his own choosing. In this way, Dundas was able to return himself unopposed until he was created Viscount Melville in December 1802. Thereafter, until his death in 1811, he made sure the Edinburgh seat went to close family connections. His memorial in St Andrew Square is arguably the most striking in the city.

The government branded the men who wanted an end to this kind of corrupt practice, ‘Radicals’ and met their requests for reform with threats and violence, arrests and exile. At the end of 1819, Parliament went a step further and passed a law restricting freedom of speech and assembly.

One group of workers who were already well organised were the weavers of Glasgow. They were not only to provide leadership in what happened but also suffer the consequences of their prominence.

On the night of 1 April 1820 a proclamation, supposedly from the ‘Committee of Organisation for forming a Provisional Government’ was posted across central Scotland. It called upon ‘all to desist from their labour from and after this day, the First of April, and attend wholly to the recovery of their Rights’.

There is no certain figure for the number who responded to this call for a general strike but it certainly ran into the tens of thousands. The army was called out, and some among the workers reacted by arming themselves – this was, after all, less than a year since 18 people had been killed by the militia at a peaceful meeting in Manchester, an event known afterwards as the Peterloo Massacre.

There were clashes, people were killed and, inevitably, the army won. Three weavers, who had led the radicals, John Baird, Andrew Hardie, and James Wilson, were executed for the part they played in the events of April 1820. Nineteen others were transported to Botany Bay.

The author, Sir Walter Scott, had other ideas about how the problem should be tackled. As these west-coast weavers said they had no work, then jobs should be found for them. Preferably something hard that gave them little time or energy for political organising and that also removed them from their community. The perfect answer was found in Edinburgh. There was a narrow path skirting Salisbury Crags. This could be widened and improved to make a pleasant walk towards Arthurs Seat. The weavers were brought to Edinburgh and set to work; an event remembered ever after in a local playground chant, “Round and round the Radical Road, the radical rascal ran…”

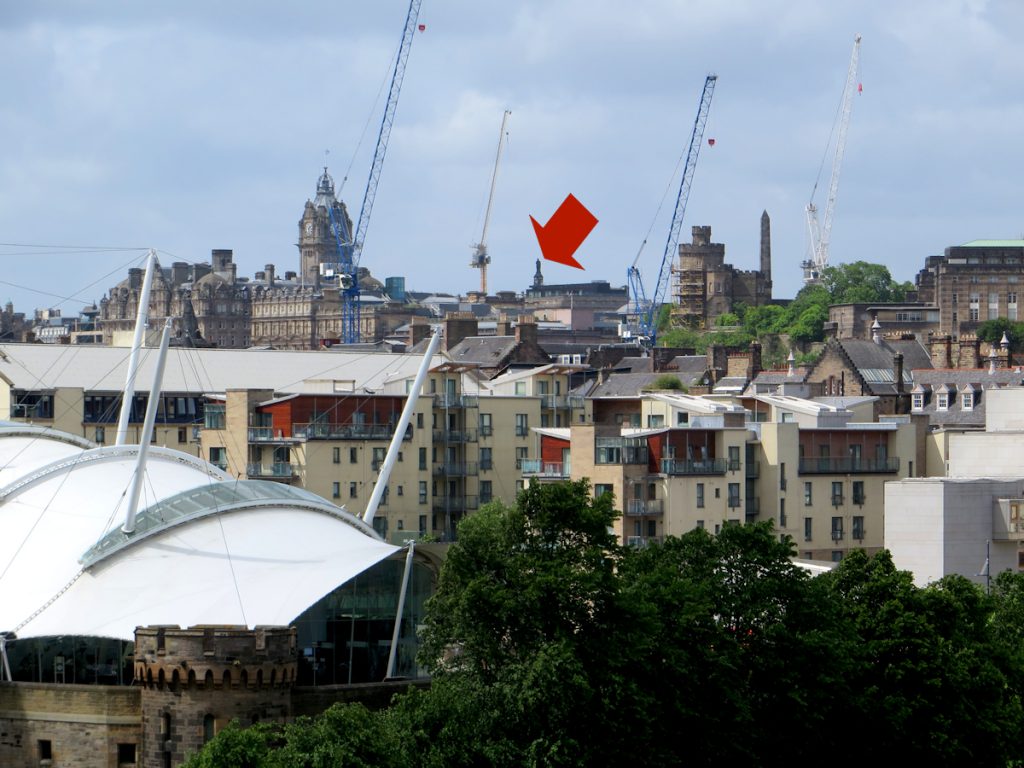

Sir Walter was well pleased with the result. He describes the view from the road in his novel, Heart of Midlothian, even though the novel is set in 1736.

“The prospect, in its general outline, commands a close-built, high-piled city, stretching out beneath in a form which, to a romantic imagination, may be supposed to represent that of a dragon; now a noble arm of the sea, with its rocks, isles, distant shores and boundary of mountains; and now a fair and fertile campaign country, varied with hill, dale and rock, and skirted by the picturesque ridge of the Pentland mountains. But as the path gently circles around the base of the cliffs, the prospect, composed as it is of these enchanting and sublime objects, changes at every step, and presents them blended with, or divided from, each other, in every possible variety of shadowy depth, exchanged with partial brilliancy, which gives character even to the tamest of landscapes, the effect approaches near to enchantment.”

It’s not known if the composer Felix Mendelssohn ever read Heart of Midlothian but he too praised the view from the road, in a letter home written in 1829. He was so impressed that he decided he wanted to live in Edinburgh and applied for the post of Professor of Music at the University. They turned him down.

The Radical Road has since featured in plays, paintings, songs and books, and the cause of the men who cut it out of the hard Dolerite stone has served as inspiration to generations of Chartists, Trade Unionists and Scottish Nationalists.

When you next walk up beneath the crags towards Arthur’s Seat, pause for a moment, halfway up, catch your breath, take in the view and remember those men who left their silent looms and came here with picks and shovels and blasting powder to create a path up the mountain. What they were asking for doesn’t seem that much by modern standards and the way they were treated seems harsh and unjust. Then, refreshed, resume your walk and stride out boldly, for you walk upon the Radical Road!

Thanks for reading, and we hope you enjoyed it. If you did, please share on social media using the buttons below.

Leave a Reply