A novel railway station

Edinburgh Waverley, or just 'Waverley' to locals, is where many, if not most, visitors arrive in Edinburgh - even the bus from the airport stops outside. It is the principal railway station in Edinburgh and the largest railway station in the UK outside London It covers some 25 acres and is set in a valley between the Old Town and the New Town on land that that has a long history.

On this page you can view some illustrations and pictures to go with the podcast of the History of Waverley, available here.

If you want to see a larger version of any illustration, right click and select, 'open in new tab' or 'view image' depending on your browser.

The City of Edinburgh c.1690

This engraving shows a view of Edinburgh from the north-east as it looked around 1690. At the top is the castle, surrounded by a curtain wall. At the bottom is the Nor Loch. Note how steep is the hill from castle to the valley.

In the bottom left-hand corner you can see Trinity College Chapel and the old Physick Garden.

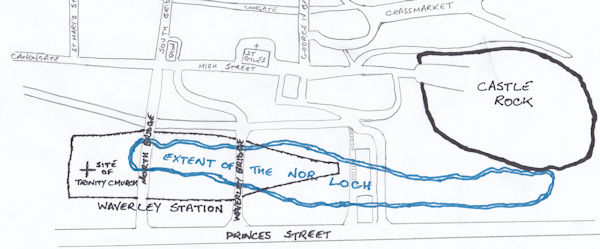

Extent of the Nor Loch

This shows the rough extent of the Nor Loch and the site of Waverley station with some of the modern street plan for ease of understanding.

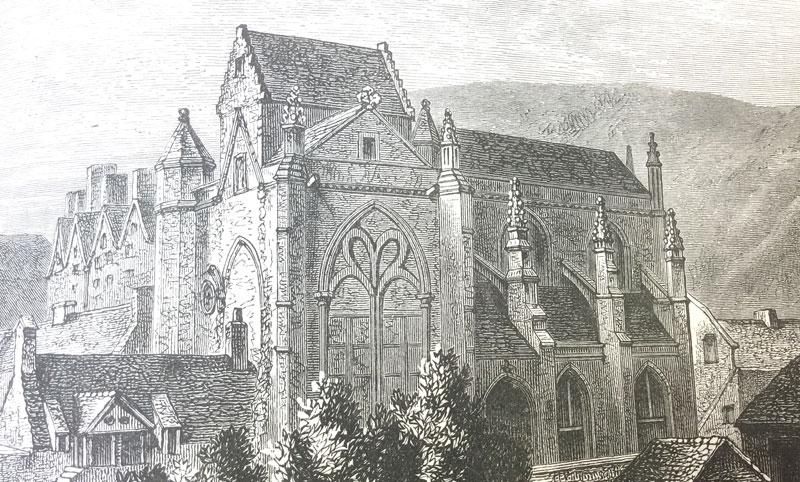

Trinity College Church

Two views of Trinity College Church and its almshouse, as they would have looked in the seventeenth century.

This was a royal collegiate church, founded by Queen Mary of Scotland (Mary of Gueldres) in 1460, in memory of her husband King James II.

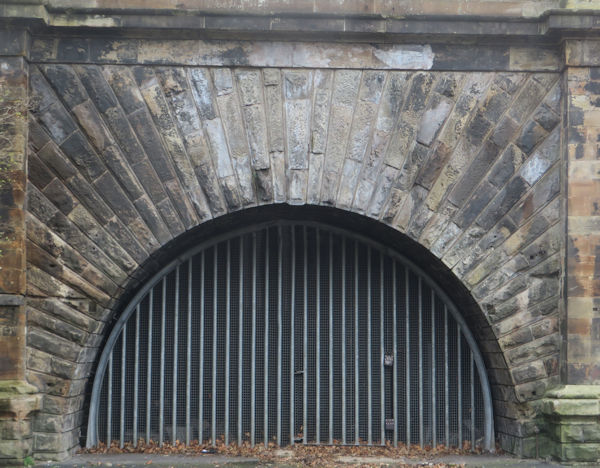

Entrance to Scotland Street tunnel

This is the sealed tunnel entrance at the north end, adjacent to George V Park.

The tunnel runs some 1,000 yards south to the site of today's Waverley Shopping Mall. The southern exit is no longer visible.

Badge of the North British Railway Company

The company arms of the North British Railway is still be seen in many places within Waverley Station. Visitors often ask, why the ‘North British’ Railway company, rather than say, the Scottish Railway Company? Inevitably, there's a bit of history behind this.

Prior to 1603, no person living in these islands would have thought of themselves as ‘British’. Indeed, for many years afterwards, the term would have meant little to most people. However, in 1603, King James VI of Scotland became the King of England. In his new realm, he would be known as King James I. He was both King of England and King of Scotland.

Though the two nations were quite different, with independent parliaments, laws, customs and currencies, James sought to unify them as much as he could. This was more to do with his ego than any desire to have the citizens of either realm regard themselves as one country. King of Britain would not suffice as a title, for this was reminiscent of the ancient Roman province of Britannia, and that had only encompassed England and Wales, for Caledonia (the Roman name for the land that would one day be Scotland) was where the empire stopped. No, James’ domains in this island were greater than that of Rome, hence, Great Britain.

Statutes of the period lay down that ships belonging to ports in South Britain should fly the red cross on a white background (the St. George’s cross), while those from North Britain should use the white cross on a blue background (St Andrew’s cross) thus clearly showing that the North and South designations were intended for Scotland and England respectively. That said, the usage never really caught on with ordinary people, and references to England as South Britain disappear very soon after, never to reappear.

In Scotland, the term North Britain was likewise abandoned, until that is, the aftermath of the Jacobite rebellions. There were many, particularly among the Scottish gentry and upper classes, and the swelling ranks of Edinburgh and Glasgow’s urban middle class, who felt that ‘Scotland’ and ‘Scots’ somehow carried the taint of disloyalty to the Crown. This was far from irrational. For a while from 1745, an additional verse had been added to the National Anthem, God save the King.

Lord, grant that Marshal Wade,

May by thy mighty aid,

Victory bring.

May he sedition hush,

and like a torrent rush,

Rebellious Scots to crush,

God save the King.

To these groups, the name ‘Scotland’ suggested a barbarous and uncivilised place. Fortunately, there was an alternative at hand: North Britain.

Nineteenth century calling cards and advertisements often refer to ‘Edinburgh, NB’ and an old guide book we have even refers to the city as ‘the ancient capital of North Britain’, as if there really had been such a country!

The North British Railway Company was therefore just one of many firms to use this construction as an ‘enlightened’ alternative to Scotland. Others included the North British Distillery and a famous Edinburgh enterprise, the North British Rubber Company, inventors of the Wellington boot!

Now, you might think that a rival company would have jumped at the chance to fill the gap left by the North British and declare itself ‘The Scottish Railway Company’ but that would be to misunderstand the innate conservatism of nineteenth century industrialists. The North British did indeed have a great competitor but that rival company chose to look even further back, and take the name of another country that had also never existed. They called themselves, the Caledonian Railway Company.