Edinburgh is rightly famed for the many excellent public houses to be found in the city. Visitors from more abstemious countries sometimes comment on the remarkable number of establishments to be found in Auld Reekie, though an early encounter with the Grassmarket at the weekend may have skewed this assessment, thanks to many guidebooks and on-line sources putting such a trip into the ‘must-do’ category.

It therefore comes as something of a surprise when we tell them that the present number of bars is probably the lowest in many hundreds of years. Indeed, were we to return to the golden age of the Edinburgh Enlightenment, we would be struck by the multiplicity of hotels, taverns, inns, public houses, ale houses, brewseats, change houses, dram shops, tippling houses and shebeens that thrived in the crowded streets and wynds, and astonished at just how much the city’s life was being carried out within them. It’s a matter of some regret that we will never know these places, except from the printed page.

However, if we might indulge a wee moment of fantasy, and imagine that a certain time-traveller came along and offered to transport us to one evening in Edinburgh in say, 1787, and did we have a suggestion of where we might take some refreshment when we got there? Well, then we have the perfect answer: John Dowie’s Tavern.

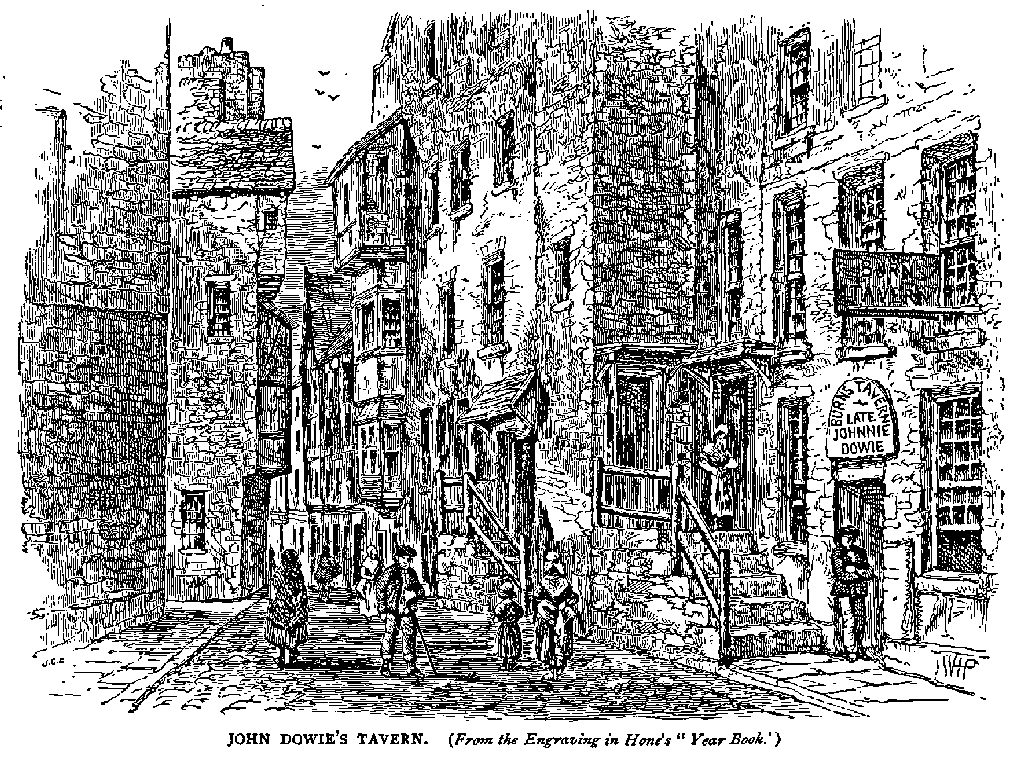

John Dowie’s was situated in the now long vanished Libberton’s Wynd, a narrow street that ran from the Lawnmarket (roughly opposite where the statue of David Hume is today) down to the Cowgate. It was thus both in the midst of the busiest part of town and yet slightly withdrawn from it.

The tavern was hugely popular, not least because ’Dainty’ John Dowie was noted as a genial and attentive host, who always managed to find some sustenance for his clientele. This would have encompassed the full range of Edinburgh folk, from the labouring poor through housemaids and valets to skilled artisans, as well as lawyers, doctors, politicians, academics, merchants, farmers and shopkeepers.

To modern eyes, the interior of the tavern would have looked cramped and somewhat unappealing. One entered into the largest room, which faced onto the wynd but was only big enough to hold fourteen people. Beyond this there were other rooms, that were really little more than windowless chambers, that required to be candlelit even during daytime, and had space for only four or six people together.

Fixed to the wall of each of these rooms was a shelf, and upon this Dowie would place the bottles as each was emptied. When it came to reckoning up the bill, he would count the bottles and charge accordingly. Inevitably, some customers would attempt to ‘play a trick’ by hiding some of the bottles but this seems never to have dented John Dowie’s good humour.

Now, all this is surely enough to recommend the place to any temporal wanderer but we have to confess to an additional interest. The tavern had been a favourite haunt of the poet Robert Furgusson, and when Robert Burns arrived in the city in the winter of 1786, he too adopted the place as his ‘local’.

Burns would meet many people at John Dowie’s but he had two special drinking companions, William Nicol and Allan Masterton, respectively the Latin master and Writing master at the High School. These three had a favoured room, one that was so small that it gained the nickname, The Coffin. They must have had some good nights there together, for Burns would later incorporate them into his song, Wullie Brew’d A Peck O’ Maut, which contains the verse:

Here are we met, three merry boys,

Three merry boys I trow are we;

And mony a night we’ve merry been,

And mony mae we hope to be!

The merriment was no doubt helped along by the local beer, Alexander Younger’s Ale, described by the writer Robert Chambers as, “a potent fluid which almost glued the lips of the drinker together, and of which few, therefore, could dispatch more than a bottle.” That bottle would have cost Burns three pennies, making it a slightly more expensive drink than the usual ‘ordinary’ ale.

Burns would remain in Edinburgh for only a short while before returning to Ayrshire but his reputation as a poet grew and grew. John Dowie was not slow to pick up on this and freely circulated a poem that he said was written by Burns, in praise of the tavern. The whole thing is some eleven verses long but just three should suffice here to give you a flavour:

“O, Dowie’s ale! thou art the thing,

That gars us crack, and gars us sing,

Cast by our cares, our wants a’ fling

Frae us wi’ anger;

Thou e’en mak’st passion tak the wing,

Or thou wilt bang ‘er.

“How blest is he wha has a groat,

To spare upon the cheering pot;

He may look blythe as ony Scot

That e’er was boru:

Gie’s a’ the like, but wi’ a coat,

And guide frae scorn.

“But thinkna that strong ale alone

Is a’ that’s kept by dainty John;

Na, na; for in the place there’s none,

Frae end to end,

For meat can set ye better on,

Than can your friend.”

John Dowie lived until 1817 and left six thousand pounds in his will – quite a small fortune for the time – so the tavern had been kind to him. His successor renamed the public house, ‘Burn’s Tavern’ and played to the growing tourist trade. Libberton’s Wynd was demolished in 1881 and if any trace of it survives, it is now below the Lothian Chambers building.

But in our imagination, there’s still an evening to be had, tucked away in a dimly-lit corner, listening to Rabbie Burns composing and carousing. If you’re reading this Doctor, we’re waiting for your call.

Leave a Reply