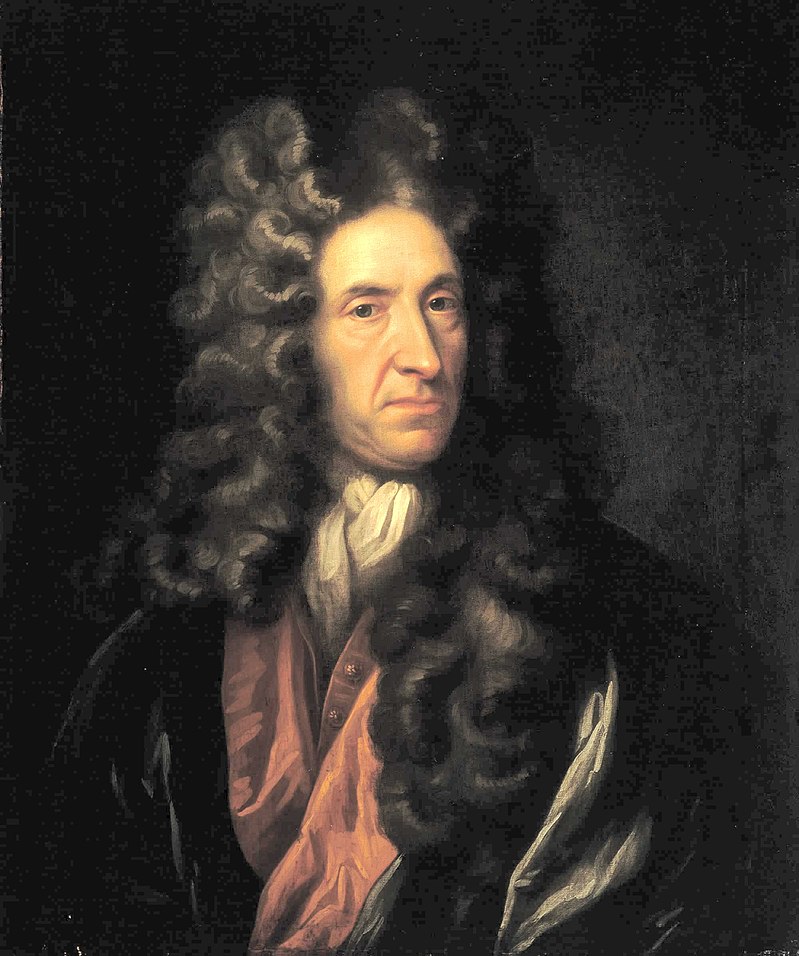

The name of Daniel Defoe is probably known to most people today through his authorship of Robinson Crusoe. However, that book was published when Defoe was fifty-nine, and by then he’d already tried his hand at one or two other professions, not the least of which was as an English spy in Edinburgh in the months leading up to the Acts of Union in 1707.

Defoe isn’t the only writer to be seduced by the cloak and dagger lifestyle – Ian Fleming, Frederick Forsyth and Graham Greene are notable modern novelists who’ve practised the dark art of espionage – but Defoe seems to be particularly suited to the job. He was born in London in 1660 as plain Daniel Foe, and later added the ‘de’ to make himself seem more aristocratic and glamourous. Not content with that, he is known to have used at least 198 different pen names in his writings. These included Solomon Waryman, William Bond, Harry Freeman and the splendid, Miranda Meanwell (which has a touch of the James Bond femme fatale about it). Clearly, he was a man who liked to hide in the shadows.

After a good education in London, Defoe set up his own business in the city as an independent trader, which sounds a little ‘Del Boy’ to modern ears and may not be too wide of the mark. By 1692, he was bankrupt, pursued by his creditors and just one step away from imprisonment in debtors prison. He turned his hand to writing and quickly discovered he had a talent for telling stories. Unfortunately for him, he also had a taste for polemics and in 1702 published The Shortest Way with the Dissenters a satirical pamphlet aimed at High Church Tories. The establishment quickly showed him that it did indeed know a short way to deal with dissent. He was arrested, tried and convicted, being fined and sentenced to three days in the pillory, followed by imprisonment at Her Majesty’s pleasure.

From Newgate Prison, Defoe wrote to a business acquaintance, William Paterson – the Scotsman who founded the Bank of England – begging him to intervene with Robert Harley, the Speaker of the House of Commons promising that he would do literally anything to get back in favour. Harley was well aware of Defoe; it was he who had started the prosecution over The Shortest Way with the Dissenters. He had a use for a man with talents such as Defoe but first let him stew in prison for six months, so that when he came out he would be really keen.

By the time he was ordered to Edinburgh in September 1706, Harley had risen to Secretary of State, the de facto Prime Minister of England, and Defoe was an experienced agent, with two years of work spying on English dissenters behind him. The instructions Harley gave to Defoe make it clear that his role was to be not just passive spy but an active undercover propagandist for the Union.

- You are to use the utmost caution that it may not be supposed you are employed by any person in England: but that you came there upon your own business, & out of love to the Country.

- You are to write constantly the true State how you find things, at least once a week, & you need not subscribe any name, but direct to me under Cover to Mrs Collins at the Posthouse, Middle Temple Gate, London. For variety you may direct under Cover to Michael Read in York Buildings.

- You may confidently assure those you converse with, that the Queen & all those who have Credit with her, are sincere & hearty for the Union.

- You must shew them this is such an opportunity that being once lost or neglected is not again to be recovered. England never was before in so good a disposition to make large Concessions or so heartily to unite with Scotland, & should their kindness now be slighted.

Defoe took lodgings at the house of John Munro, at the sign of the Half Moon by the Netherbow. From here, he wrote back to tell Harley that Edinburgh was in a state of uproar, with mobs on the street giving voice to their clear opposition to the Union.

“I… Saw a Terrible Multitude Come up the High Street with A Drum at the head of Them shouting and swearing and Crying out all Scotland would stand together, No Union, No Union, English Dogs, and the like.”

Defoe claimed that a rock was thrown at him as he looked out of the window and that his life was in danger (something his masters in London doubted) but could not help himself in boasting about how good he was at deception.

“I am Perfectly Unsuspected as Corresponding with anybody in England… To the Merchants I am about to Settle here in Trade, Building ships etc. With the lawyers I Want to purchase a House and Land to bring my family & live Upon it (God knows where the money is to pay for it).

“With the Glasgow Mutineers I am a fish Merchant, with the Aberdeen Men a woollen and with the Perth and Western men a Linen Manufacturer, and still at the End of all Discourse the Union is the Essentiall and I am all to Every one that I may Gain some.”

He told other men he was a glass-maker, to some he claimed he was a salt-maker and even styled himself a gentleman of property. To have got away with this, in the tight packed community of Edinburgh at the time, is a testament to Defoe’s power of imagination and ability to get on well in company.

By mixing with the people of the city, Defoe was able to pass back to London, comments that would not make it back through more formal channels. When he heard talk that the Union would lead to increases in the cost of beer, he advised that something be placed in the Explanation of the Acts about the Union bringing down the cost of malt. He was also able to tell London that the majority of the 1500 Scottish soldiers the government thought they could rely on were disaffected and suggested that English troops be brought up to the border, ready to invade at a moment’s notice. Happily for all, this advice was not heeded.

Defoe also carried out the second part of his remit and began publishing leaflets. These were distributed in both London and Edinburgh. However, the arguments made in these were far from consistent. Those in England stated that the Union was wholly to the advantage of the English. It would remove the ever-present threat from the north, while gaining Scotland’s manpower and resources and boosting England’s prestige on the world stage. The Scots were relatively few in number compared to the English, he wrote, and the latter would soon come to dominate them in matters of church and state.

Those published in Edinburgh took the opposite view. Scotland’s church and state would be forever guaranteed by the Union. England’s firm parliamentary roots would ensure that Scotland would never be dominated by its larger neighbour and that the markets of the world would now be open to Scottish merchants with great benefits to trade. Never again would countries such as France drag Scotland unwilling into costly wars with England. It would be peace and prosperity for all time. Both sets of leaflets were purported to be written by loyal Englishmen or true-hearted Scots as the case may be. In reality, they all came from the pen of Daniel Defoe. Fake news is nothing new.

Defoe was not the only pro-Union spy in Edinburgh, or Scotland, and the fact that the powers in London thought it worthwhile to try and persuade men and women who had no vote and could not therefore influence the outcome of the negotiations shows how much they feared a rebellion among the common people. Such an insurrection could throw up leaders that were not so open to persuasion through titles and honours as were the Scottish nobles they were currently dealing with; the men that Robert Burns would later characterise as ‘A parcel of rogues’.

The treaty of Union passed through the Scottish Parliament in early January 1707 as the bells of St Giles rang out the tune “Why should I be so sad on this my wedding day?” Defoe stayed on in the city, hoping that his services would be rewarded with a plum job in the new administration. He did not get his wish. Harley in London was ill and too busy fighting with rivals over control of the new, joint parliament. Besides, as he had shown earlier in keeping Defoe in prison, he knew how to manipulate the man. He thought it better to have Defoe relying on the uncertain and inconsistent payment for spying, rather than in the safety and comfort that a regular salary would bring. He simply ignored all the correspondence arriving almost daily from Edinburgh.

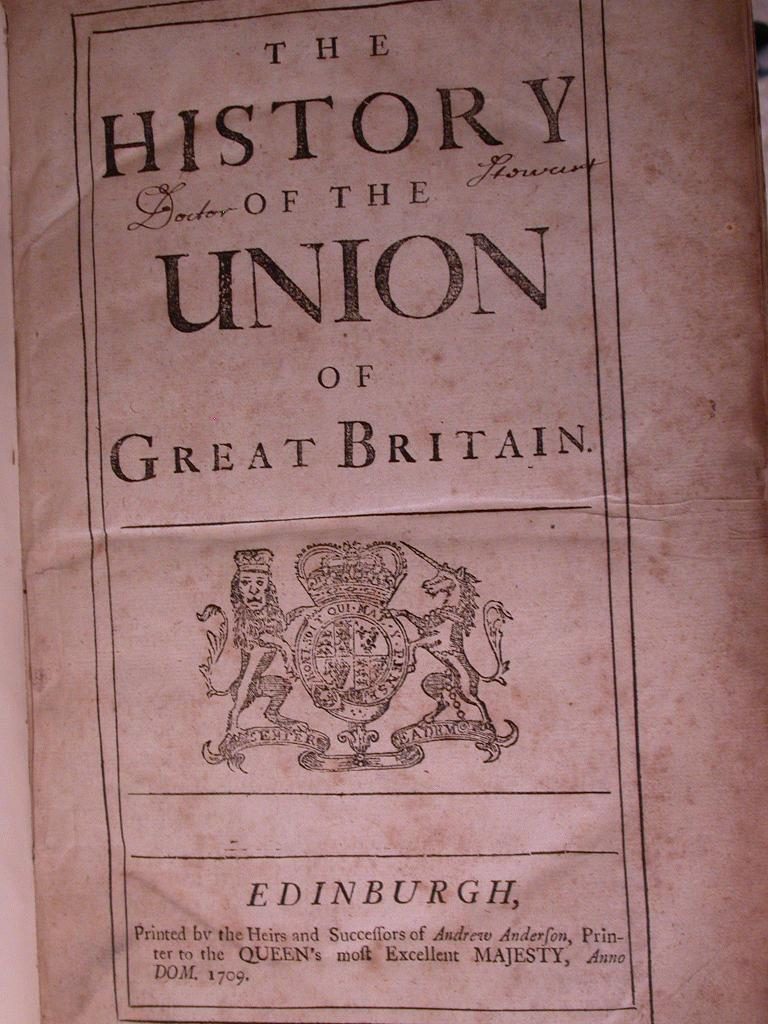

For Defoe, the funding from London was a lifeline (though he worried that Harley might not approve of the way he was spending it and demand repayment). In April 1707, he joined the Edinburgh branch of the Society for Reformation of Manners, a group that gave him access to the city’s merchants. He traded in salt, linen, horses, wine and brandy. He also announced that he was writing the History of the Union. This was all a cover for what he was really about: the life of a secret agent.

Defoe made no money in his various ventures and by November 1707 he was in debt and the letters to London were getting increasingly hysterical. He feared returning to England without permission and wrote pointing out that Edinburgh was not like London. “Pen and Ink and Printing will Do Nothing here. Men Do Not live here by Their Witts.” As Defoe had little else, he was clearly in the wrong place.

Harley relented and sent him £100 (for which he signed the receipt ‘Claude Guilot’). He left Edinburgh at the beginning of December and arrived home in London on 1 January 1708.

The History of the Union was published the following year, though rather inevitably, it’s now seen as a very one-sided account. Defoe returned to Scotland in 1726 and concluded that the improvement in trade and the economy that he had foretold twenty years earlier had not come about – it was “not the case, but rather the contrary”, he wrote.

Harley was feted with honours. He was created Earl of Oxford and made Lord Treasurer and Knight of the Garter. His political enemies caught up with him when the crown passed from Queen Anne to the Hanoverian George I. He was imprisoned but escaped impeachment by retiring from politics.

Daniel Defoe went on to be a successful writer. Not only was there Robinson Crusoe but also Moll Flanders and Roxana: The Fortunate Mistress among others. These books are among the first true novels in English and a terrific read even today. Despite this, his talent for striking a bad deal never left him and he spent long periods in debtors’ prison. He died in 1731, in hiding from his creditors.

Leave a Reply