Walking through the Dean Cemetery the other day, we stopped at a particular family memorial. It was one that we’d visited many times before, for reasons that we’ll come to, but it also seemed a suitable jumping off point for a blog post about a once great British institution that had its roots here in the city. A small product of Edinburgh on which, for more than 150 years, the sun never set – Blackwood’s Magazine.

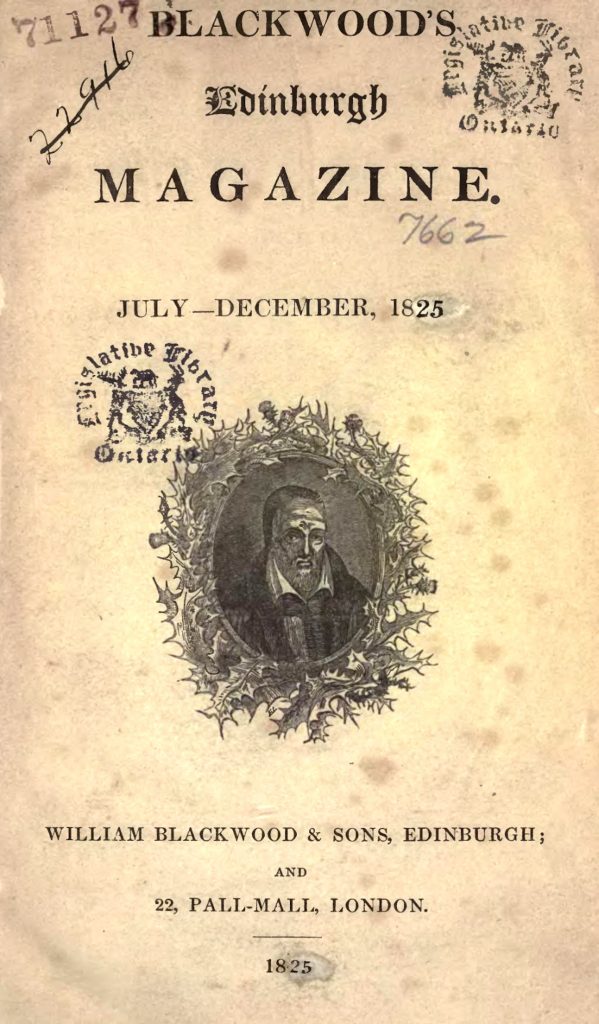

Edinburgh in the early nineteenth century was a major centre of printing and publishing. Thus, when William Blackwood first published his new magazine in 1817, he was entering a thriving market. There was already the Edinburgh Review, a broadly Whig supporting paper, and the weighty and firmly establishment Quarterly Review. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine took the side of the Scottish Tories, and even a modern reader would recognise its mix of pro-union and pro-empire tales of military and colonial life to be more than a little partisan.

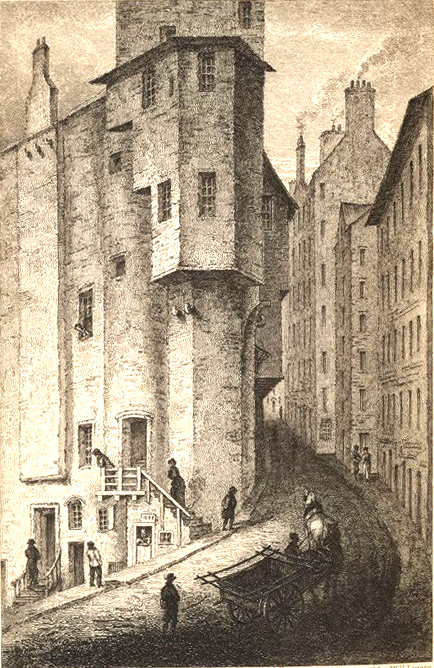

William had been born in Edinburgh in 1776, and, at the age of 14, became apprentice to a bookseller in the city. In 1804, he opened his own shop on South Bridge selling ‘Old, Rare and Curious Books’. Business was good and in 1816 he moved his premises to Princes Street; it was from here that Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine (for the first six editions entitled the Edinburgh Monthly Magazine) was published.

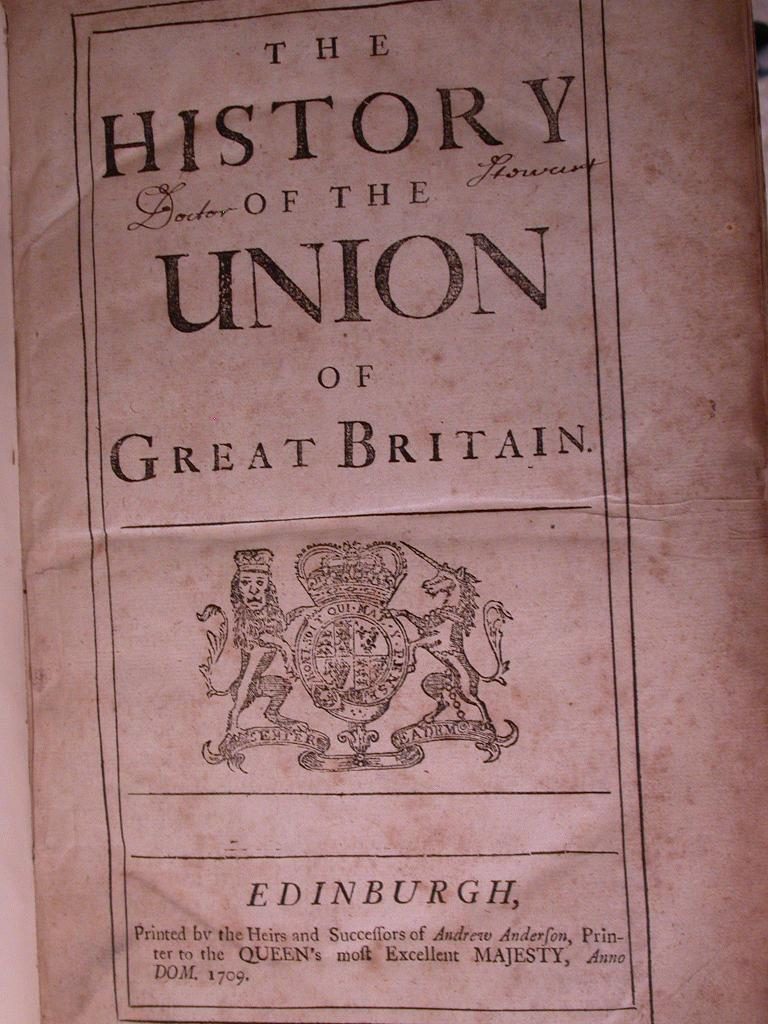

The first edition set out what a new reader might expect. Blackwell intended to publish extracts of memoirs, original verse, travelogues, antiquarian writings, reviews, synopses of parliamentary speeches, history (particularly Scottish history), and foreign affairs. At this stage he had not considered including original fiction. The cover featured a portrait of George Buchanan, a sixteenth century Scottish historian (which many no doubt took to be the likeness of William Blackwood). As a dealer in old books, Blackwood would no doubt have come across the works of Buchanan and, by choosing his face for the cover, he was linking this new publication to an old tradition – one that was firmly Scottish and staunchly Presbyterian.

The Scottish writer Thomas Pringle, (who would later emigrate and gain fame as the first English language poet of South Africa) was initially employed as editor but Blackwell quickly fell out with him and took over the job himself.

Despite its Tory leanings, Blackwood’s considered work from a wide variety of sources. Maga, as it liked to style itself, published works by Coleridge and Shelley at a time when both were considered very radical. The magazine also championed James Hogg, known as the Ettrick Shepherd, and published some of his early work, though Blackwood would later turn on him and publish vicious and thinly disguised parodies of his prose.

Blackwood recognised that he had tapped into a growing desire for intellectual reading matter among the growing middle and professional classes, and pioneered a certain form of short story in the English language. This style would become a major influence on later Victorian writers such as Charles Dickens and the Brontë sisters.

The magazine was also one of the earliest exponents of Terror Fiction, such as the tale Buried Alive published in 1821. Edgar Allen Poe was particularly influenced by these sensationalist stories and Robert Morrison and Chris Baldick in their 1995 collection Tales of Terror from Blackwood’s Magazine describe these tales as the missing link between the Gothic tradition of the late eighteenth century and Poe’s short horror fiction.

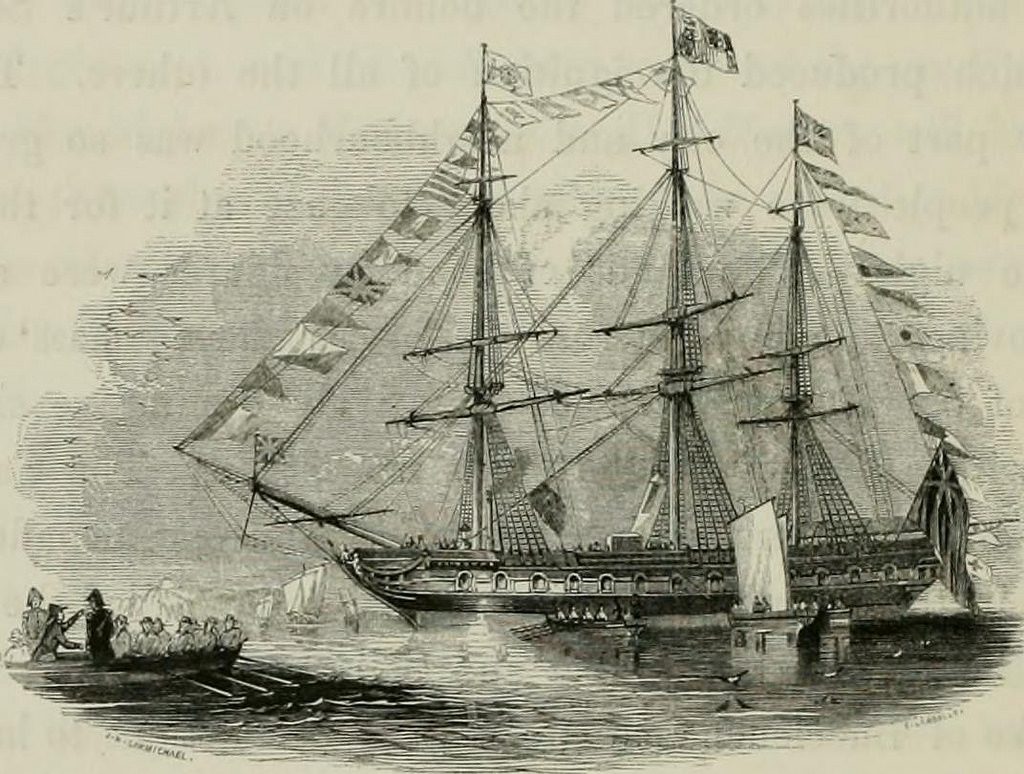

In 1830, William moved from Princes Street – which he considered had gone downmarket (where have we heard that before?) – to the more prestigious George Street. By now, copies of Blackwell’s Edinburgh Magazine could be found in every corner of the British Empire from the wardrooms of Royal Navy ships on the China station, through the houses of tea planters in the hills of India to the Officers Messes of Army barracks sweltering in the African sun.

William had seven sons, five of whom played a part in running both the magazine and the wider publishing business. His sixth son, John, became editor in 1845 after working in Blackwell’s London office for some years. John had an eye for good writing and when one day an anonymous manuscript crossed his desk eagerly he accepted the offer to publish. The work was Scenes of Clerical Life by Mary Ann Evans, better known by her pen name of George Eliot.

To his credit, when John discovered the piece had been written by a woman it made no difference to his decision. George Eliot was so grateful she went on to publish all but one of her novels, in serial form, through the magazine. Other authors whose early works found a home in the pages of Maga would include John Buchan and Joseph Conrad.

In 1905, the magazine moved to London and dropped ‘Edinburgh’ from the title, becoming simply, Blackwood’s Magazine. It would continue in popularity for some years but was increasingly seen as a bit old-fashioned and staid. In his essay, The Lion and The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius, George Orwell would write, “If you were a patriot you read Blackwood’s Magazine and publicly thanked God that you were ‘not brainy’”.

In 1940, the London offices of Blackwood’s Magazine were burned out during a Luftwaffe air raid – a sight seen from 25,00 feet by Douglas Blackwood, an RAF fighter pilot and great-great-grandson of William Blackwood. The firm never really recovered, though it continued to publish until the last edition was printed in 1980.

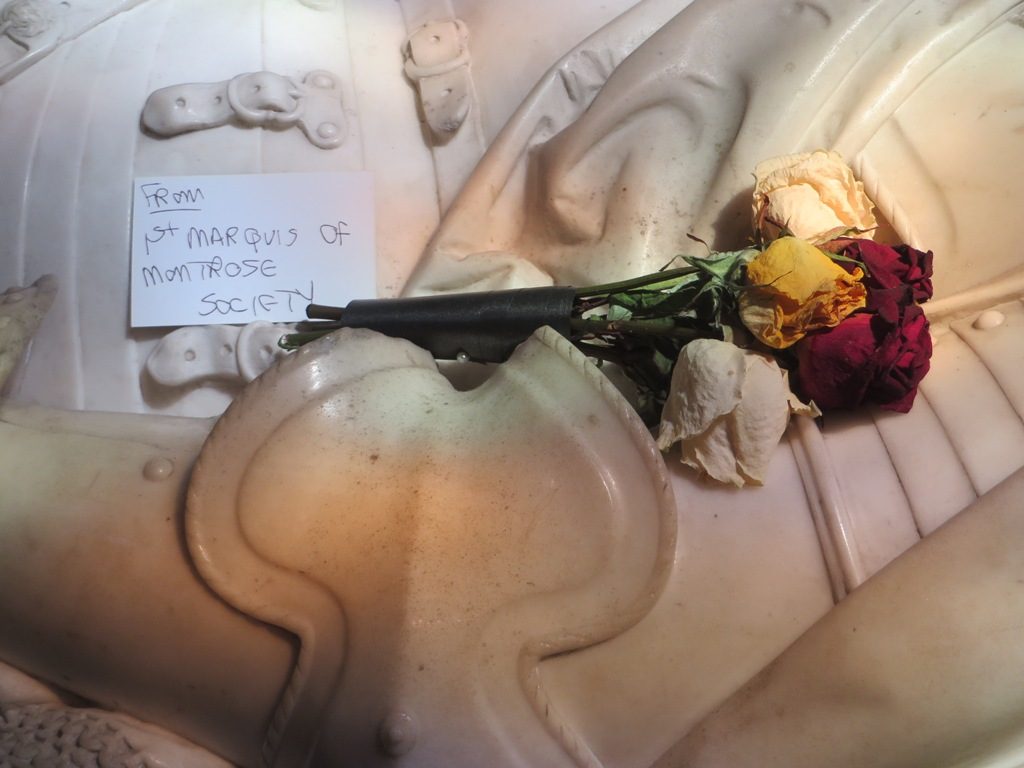

The memorial in the Dean Cemetery that we mentioned at the start of this blog, is the resting place of John Blackwood, the man who recognised the genius of George Elliot. It is modest, by Victorian standards, and devoid of the fulsome praise of the life, manners and conduct of the deceased, so favoured by other gravestones of the period.

We have returned to it many times and shown it to visitors because, in a small way, it marks the change from the optimism and expansion of the 19th century to the brutal realism and decline of empire through the 20th. A movement that was mirrored by the rise and fall of Blackwood’s Magazine. To the right, as you look at the memorial, you can see a simple wooden cross set into an unadorned stone slab. It’s looking worse today than it did when we first saw it 25 years ago, though that’s not surprising as it is now over 100 years old. The inscription around it is difficult to read but we’ve transcribed it, and it tells its own story.

AUBREY BLACKWOOD PORTER

Grandson of John Blackwood, Lieutenant 4th Battalion 2nd Highland Light Infantry

Killed in action at Loos France 3 October 1915 Aged 24

This wooden cross was sent from France where it stood on his grave in the British Military Cemetery at Vernelle previous to the placing there of the headstone which now marks the grave of British soldiers killed in France in The Great War 1914 – 1918

Placed there in honoured and loving memory by his mother