This is by way of a quick, midweek update to the last post regarding James Tytler. There were a couple of questions that came in, and here are the answers as best we know them.

Q1. What was the balloon made of?

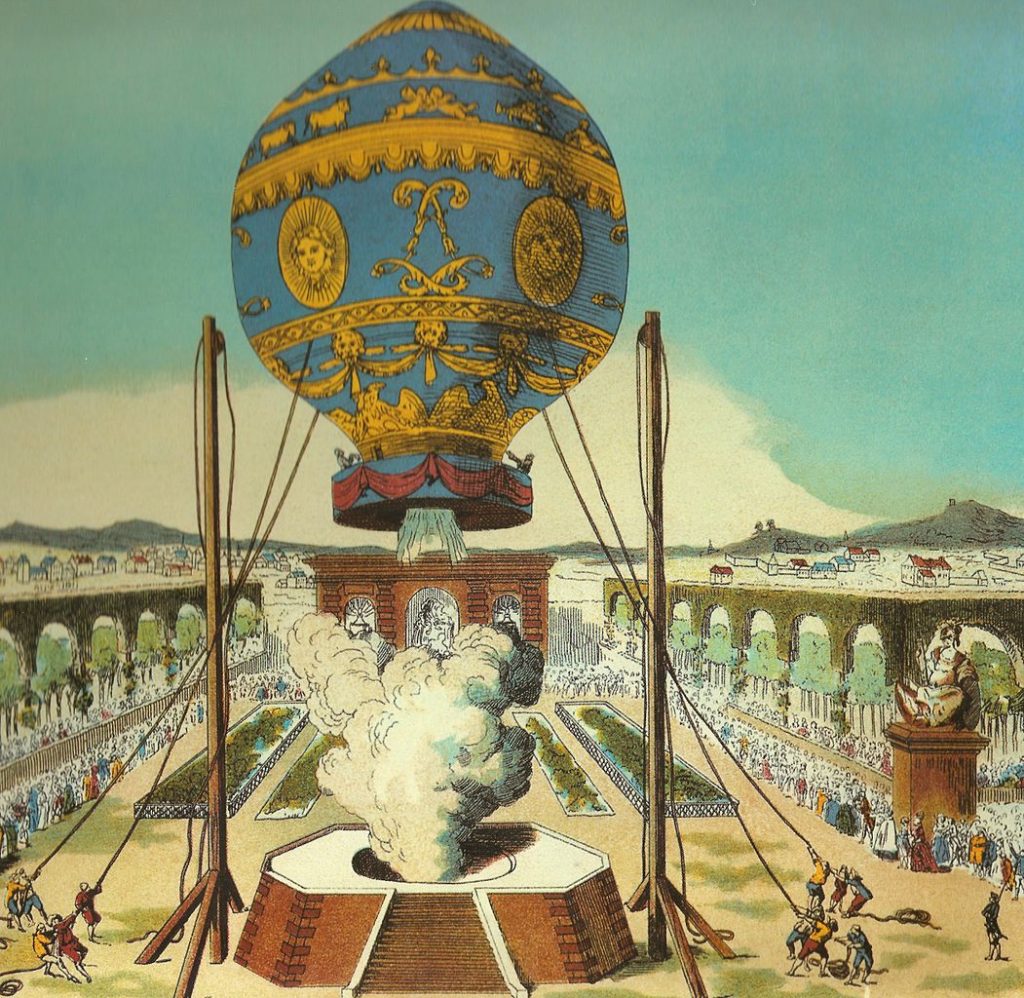

Well, we’re not entirely certain. Tytler would have known about the construction of the Montgolfier balloon in France. This was made of taffeta, coated inside with a varnish of alum, as a fire retardant. The exterior was painted with rich blue and gold decoration. The cash-strapped Tytler could not hope for anything so fancy.

The Great Edinburgh Fire Balloon was made of cloth, and linen is the most likely candidate. Due to earlier problems, a coat of varnish was applied before the first actual flight. The envelope was not enclosed by a net but seemingly an open frame of ropes that met and enclosed the ‘boat’ below. Incidentally, the boat part never made it off the ground. It was destroyed by the unhappy mob on August 6, after Tytler failed to ‘rise to the occasion’. Ever the man of resource, he secured “One of the small baskets in which earthen ware is carried.” So he was probably sitting in something very like a modern wash basket for those first flights.

Q2. Why did he fly in August? As a local, he must have known the Edinburgh weather was notoriously capricious in that month?

Tytler chose August 6, 1784 because it fell in the week of Leith Races. These were the most important sporting event held in Scotland at the time and attracted huge crowds. He must have thought that with the city packed full of pleasure seeking gamblers and sportsmen, he would draw the biggest crowd.

Q3. Is there a painting or illustration of the flight?

Not to our knowledge, and certainly not contemporary to events. Tytler originally planned to carry a stove within the basket that would have kept a ready supply of hot air going into the envelope. He looked at ‘lightweight’ fuels such as sulphur-infused sheep wool (imagine the smell when that burned!) that could be carried on board but ultimately, the volume of hot air inside the envelope was barely sufficient to lift itself and Tytler, so the stove had to go. This meant that the flights were really little more than short hops before the air inside cooled down. Nevertheless,they were remarkable for their day and are recognised as the first true, manned flight in Britain. It’s just that any artist would have had to be very quick on the draw.

The Edinburgh artist John Kay did do an engraving entitled ‘Fowls of a Feather Flock Together’ showing Tytler meeting the Italian balloonist Lunardi but the balloons illustrated in the background are nothing like all the other descriptions of the Great Edinburgh Fire Balloon and may be discounted.

Remarkably, James Tytler met Robert Burns and it is from Burns that we have the best description of Tytler, the man. On 13 November 1788, Burns wrote to his friend Mrs Dunlop, back in Ayrshire. In a long letter about collecting songs for The Scots Musical Museum, he mentions James Tytler. “A mortal, who though he drudges about Edinburgh as a common printer, with leaky shoes, a sky-lighted hat, and knee-buckles as unlike as George-by-the-grace-of-God and Solomon-the-son-of-David, yet that same unknown drunken mortal is author and compiler of three fourths of Elliot’s pompous Encyclopedia Britannica.” The expressed mixture of pity and astonishment seems to be the near universal view of Tytler by his contemporaries.

Thanks for reading and if there are any more questions about Tytler, or any of the other topics we’ve covered, please do get in touch via the Contact page, and please do share these posts via social media.

Leave a Reply